Garden Planting Calendar

Planning a vegetable garden can feel like a monumental task. You have to know your USDA planting zone. You have to research to know which plants can reasonably grow in your climate. You need to know your first and last frost dates.

Then, you need to compare that data to against all the planting requirements for every vegetable you want to grow. You have to sort out which plants go in the ground before the last frost, which need to wait until risk of frost is past, and more. Even if you live in a frost-free planting zone, you still need to decide which plants are grown during your cool season and which can be summer grown.

Or, you can save yourself a lot of time and use our vegetable garden planting calculator!

Then, you need to compare that data to against all the planting requirements for every vegetable you want to grow. You have to sort out which plants go in the ground before the last frost, which need to wait until risk of frost is past, and more. Even if you live in a frost-free planting zone, you still need to decide which plants are grown during your cool season and which can be summer grown.

Or, you can save yourself a lot of time and use our vegetable garden planting calculator!

1. Enter Your USDA Plant Hardiness Zone

Start by entering your USDA plant hardiness zone. In case you don’t know it, then use our look-up tool to find it. By entering your hardiness zone, only plants that can be reasonably grown in your planting zone will appear on your customized planting list.

2. Enter Your Frost Dates

Next, if you live in zones with frosts and below freezing temperatures, you’ll also have to enter your first and last frost dates. If you don’t know those dates, we have a look-up tool for that too.

Frost Planning Tip

If you want to be even more accurate, ask gardeners or the agricultural extension office in your area what dates they typically use for planning their calendars. For example, in my area, our average last frost date is in late April. Yet, everyone around here uses Mother’s day as the start date for our warm season plants.

We may not have frosts past April. But our nights are still so close to freezing, that the soil is slow to warm. So, using a slightly later last frost date actually gives gardeners in my area much better results than average last frost dates.

In other climates, though, if you tried to use the same logic, you might miss your planting window on cool season crops. So, try to find the best dates you can for your local area.

3. Print Your Planting Calendar

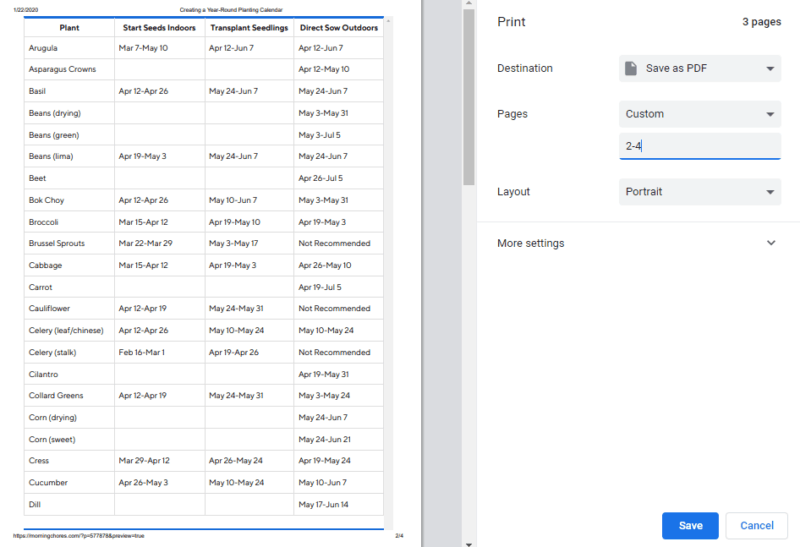

Once you enter that information, click submit. Your custom vegetable planting will appear.

Then, you can click the print icon at the top of the page (to the right of my name Tasha Greer) to print your custom calendar. Then, you can exclude most of the text of this post by narrowing the page number selection before you print. That will give you a tidy calendar to mark up with your own data.

Now, that you have a great starting point for planning your calendar, you still have some work to do. You’ll need to decide if you will grow transplants in cells or soil blocks and then put them in the garden. Or you’ll need to decide if direct planting is better for you.

Many gardeners use a mix of transplanting and direct planting to get the best results in their garden.

Starting Seeds Indoors

Starting seeds indoors and transplanting will get you a jump on the gardening season in many cases. It also cuts down on weeding while you wait for your seedlings to emerge and grow large enough to crowd out weeds. That can make managing a large garden much less work.

The planting calendar indicates a date range for starting indoors and then transplanting outdoors. The earliest date for indoor seed starting corresponds to the earliest date for outdoor transplanting.

Note: If you don’t start seeds at their optimal soil temperatures, it may take longer for seedlings to germinate and grow to transplant size.

What if There’s No Transplanting Dates?

You’ll also notice that some of the transplanting dates are blank. Many of those plants can be safely started in 1.5-2 inch soil cells or blocks and transplanted. However, there’s still no consistent data on when to start indoors and when to transplant.

In my own trials of transplanting, I’ve found that even when I get a 6-week head start on things like beets, turnips, and carrots, my much later planted in-ground seedlings are always harvest-ready before my transplants. Also, summer squash and beans start producing 2-4 weeks slower than direct planted seeds.

For that reason, we’ve left those columns blank. However, if you do your own trials and find that transplanting those plants is beneficial for increasing your productivity, then use those blank spaces to record the dates that work best for you.

Direct Seeding Not Recommended for Some Plants

In some cases such as tomatoes and eggplants, you can directly seed them outdoors, but they will simply grow better if you start them in containers and transplant them deeper than their original container height.

This allows the plants to get a warm start and then grow adventitious roots to help increase production. It can also help minimize risks from early season fungal pathogens.

For those plants, you’ll see “not recommended” in the direct seed dates.

That doesn’t mean you can’t or shouldn’t do it. It just means you’ll need to do some extra calculations to figure out when to plant to time around common plant diseases, pest issues, and temperature fluctuations that stress young plants.

Comments

Post a Comment